A Large Tumor—

Esophagram shows a large 6 cm tumor disrupting mucosa and causing a narrowing of the lumen.

Endoscopic ultrasonography is a new technique used to evaluate the gastrointestinal tract and contiguous organs High resolution endoscopic ultrasound dramatically improves tumor characterization, and enables more precise TNM staging. The earlier diagnosis achieved with this technique combined with more precise staging, permits the most effective timing and selection of chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and surgery. This new technology will almost certainly have great impact on the clinical outcome of patients with gastrointestinal tumors.

Endosonography or endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) is a diagnostic modality that combines and modifies techniques of gastrointestinal endoscopy and ultrasonography. The concept behind EUS is to diminish the distance between the ultrasonic source and the organs to be imaged. An ultrasound transducer is incorporated into the tip of a fiberoptic endoscope. While endoscopically visualizing the lumen, the probe can be guided and placed adjacent to the area of disease, thus avoiding bones, adipose tissue, and airfilled structures, all of which limit sound wave imaging clarity. The short distance between the ultrasonic source and the target permits the use of high frequency, high resolution sound waves which, due to their shorter penetration depth, are not suitable for transcutaneous ultrasonography.

Current endosonography instruments use frequencies of 7.5 and 12 MHz, as compared to 3.5 MHz for regular ultrasound and 5 MHz for blind rectal and esophageal probes. For the gastrointestinal wall and adjacent organs, the resolution of the images produced by these high frequency sound waves is unmatched by any other imaging methods.

Since the development of endoscopic ultrasound in 1980, many symposia and studies have evaluated the application of the technique in clinical practice. 1-10 EUS has been used to study the gastrointestinal wall as well as organs in close proximity to the gastrointestinal tract. Reports have repeatedly shown that endoscopic ultrasonography results in a significant advance in nonoperative gastrointestinal tumor characterization. EUS is, at present, the most accurate method of clinically staging neoplastic disorders of the gastrointestinal tract. It is not only essential for staging, but can also provide unique diagnostic information, often otherwise obtainable only by laparotomy or resection.

Prior to about 10 years ago, therapeutic options for the treatment of intestinal tumors was limited, so accurate nonoperative staging had limited clinical use. Surgery for resection, palliation, or staging was usually attempted in all but the most advanced cases. In general, chemotherapy or radiotherapy of gastrointestinal cancers had been disappointing because these solid tumors have both cycling and noncycling phase cells, and generally have low growth fractions. Also, by the time gastrointestinal tumors were detected, their growth fraction had declined markedly, resulting in decreased sensitivity to antineoplastic agents that selectively kill actively dividing tumor cells. 11 More recently, however, effective combinations of chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and surgery have resulted in increased response rates and improved survival.12-20 Studies indicate that the most effective timing and dosage of these treatments depend on accurate staging. Therefore, precise staging can now have great impact on patient outcome. Accurate staging with endoscopic ultrasound should also improve clinical trial assessment of new chemotherapeutic agents and combination treatment protocols.

Endoscopic ultrasonography has been used to stage esophageal carcinoma, 21,22 gastric carcinoma, 23-25 submucosal tumors, including lmphomas of the stomach, 26-29 pancreatobiliary tumors, 30-35 and carcinoma of the rectum and colon. 36-39

Each of these applications will be reviewed, with emphasis on the clinical utility of endoscopic ultrasound and planning chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and surgery. Definitions for stages of tumors are according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer using the T (primary tumor), N (regional lymph node), M (metastasis) system. 40

The Instruments

The most widely used and reliable endosonography instrument is the Olympus GF-EUM3 imaging unit.41 The scope is 130 cm in length and can be passed into the distal duodenum. This instrument is dedicated solely to EUS and cannot be interfaced with other conventional ultrasound consoles. Because the GF-EUM3 echoendoscope has a rigid tip 4.2 cm in length, endoscopic maneuverability is more difficult than with standard endoscopes. The oblique viewing optics make endoscopy with the echoendoscope similar to that with a side viewing endoscope.

The large, 12.6 mm diameter of the echoendoscope shaft restricts passage through a significant number of strictures. While a prototype endoscopic echoprobe, 42 which can pass through many strictured areas, can be inserted through the 3.5 mm biopsy channel of a standard therapeutic endoscope, the very small acoustic field of view and limited penetration of the 20 MHz sound wave frequency limits the accuracy and utility of this probe.

Endoscopic Ultrasound Technique and Image Orientation

Image interpretation requires a thorough knowledge of anatomic relationships of intraabdominal vessels and organs, as well as an understanding of the general principles of ultrasound imaging. 43-45 The echoendoscope is inserted like a standard endoscope into the upper gastrointestinal tract. Like standard endoscopy, the procedure can be performed easily in an office or other outpatient setting. Pharyngeal anesthesia and intravenous sedation are generally used, but not required.

Under direct vision, the echoendoscope is passed to the target area, and intraluminal gas is aspirated. The area to be imaged is then brought into sonographic focus by filling the balloon surrounding the transducer at the tip of the echoendoscope with about 15 cc of water and interposing this non-attenuating acoustic coupling medium between the transducer and the surface of the gastrointestinal wall. If the target area is in the gastrointestinal wall itself, water is generally placed directly in the lumen for optimal acoustic coupling. The exact technique will vary according to the indications and objectives of the examination.

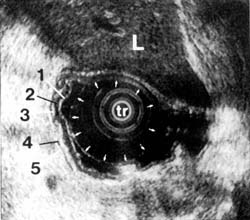

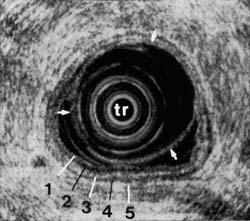

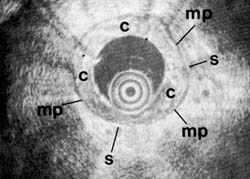

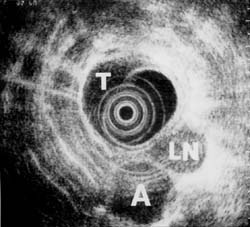

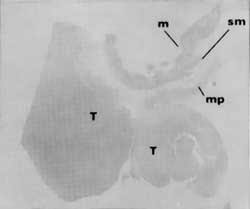

On endoscopic ultrasound, the gastrointestinal wall appears as five layers 46 (Figure 1). The first layer is hyperechoic and corresponds to the superficial mucosa. The second layer is hypoechoic and corresponds to the deep mucosa. The third layer is hyperechoic and corresponds to the submucosa plus the acoustical interface between the submucosa and the muscularis propria. The fourth layer is hypoechoic and corresponds to the muscularis propria minus the acoustical interface between the submucosa and the muscularis propria. The fifth layer, the serosa and subserosal fat, is hyperechoic.

Optimal imaging of the gastrointestinal wall is essential to determine the wall layer(s) involved by the disease process. To achieve optimal imaging and limit artifact, the sonographic plane must be placed as close as possible to being perpendicular to the intestinal wall. Endoscopic: ultrasound images of organs contiguous to the gastrointestinal tract each have their own characteristic appearance.44,45 This includes large vessels and lymph nodes. Malignant lymph nodes will generally appear hypoechoic and round, with sharp margins. Benign lymph nodes appear irregular in shape, have indistinct margins, and have mixed internal echoic features. 47

Figure 1A

Figure 1B

Figure 1C

Endoscopic Ultrasound Imaging of Esophageal Carcinoma

Standard fiberoptic endoscopy allows direct visualization and biopsy of an esophageal lesion, but is not accurate for assessing tumor depth and extent. 47 With EUS, on the other hand, one cannot only directly visualize the lesion's surface, but also the relationship of the lesion to extra-esophageal mediastinal structures, such as the aorta, trachea, and heart. A limiting factor for esophageal endosonography is that, in up to 25% of patients, the instrument will not pass the stenosis. 22,49 Nevertheless, even in these patients, partial staging can be obtained. Overall, EUS significantly improves the accuracy of staging and resectability status of tumors that, as determined by computed tomography (CT), have not metastasized.

Depending on the population being studied, EUS is at least 50% more accurate than CT in evaluating the T and N stages of esophageal carcinoma. In general, the less extensive the disease, the greater the difference in accuracy between endoscopic ultrasound compared with CT.22,49 Numerous studies 50,51 have shown that CT is not reliable for differentiating stage I from stage II, or even stage III disease. Only endoscopic ultrasound can reliably determine the extent of local disease, including spread to regional lymph nodes .22

Most published reports 52 agree that resection of stage I esophageal tumors provides the best form of palliation and the only possibility of cure. However, once advanced stages are present and the esophageal wall is breached, or there are metastases to lymph nodes, survival for patients treated only with surgery is substantially reduced. Radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and endoscopic therapy, including laser therapy, are alternatives to surgery for palliation, especially for the patient who is a poor operative risk or who has evidence of extensive local disease. The best results have been reported combining chemotherapy and radiotherapy with surgery, with as high as a 36% five-year survival achieved by Hilgenberg et al. 13 Endoscopic ultrasound is the most accurate means we have of detecting tumors that have breached the wall or spread to lymph nodes, and thus better identifying candidates for chemo- and radiotherapy protocols .22,23

* Case Reports of Staging Esophageal Tumors-Following are some clinical examples of how endoscopic ultrasound can improve staging of esophageal cancers. Figure 2A shows a small flat tumor at the distal end of the esophagus as seen on endoscopy. Esophagram showed only minimal inflammatory changes and CT did not reveal any evidence of tumor. However, endoscopic ultrasound showed a small tumor that had invaded adventitia in one area. More significantly, EUS visualized many lymph nodes that met the criteria for metastatic disease (Figure 2B). For this reason, surgery was postponed while chemotherapy and radiotherapy were instituted.

Figure 2A

Figure 2B

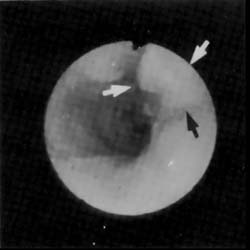

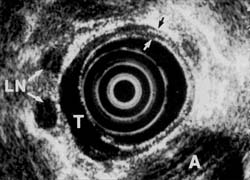

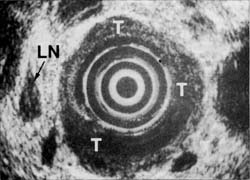

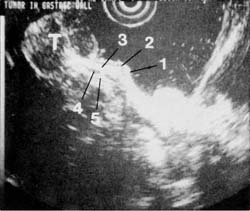

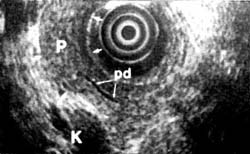

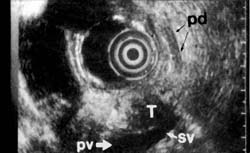

In contrast, another patient (Figures 3A and 3B) with similar symptoms had a long, 6 cm tumor visualized on esophogram. Endoscopy confirmed the radiologic findings and CT suggested possible lymph node spread. Endoscopic ultrasound, however, showed that the tumor growth was primarily towards the lumen and that, although the muscularis propria was involved, there was no penetration into adventitia. In addition, endoscopic: ultrasound indicated no evidence of spread to lymph nodes. The single enlarged lymph node noted on EUS did not meet other criteria of malignant disease. These findings were confirmed at surgical resection. The enlarged lymph node proved to be inflamed due to silicosis.

Figure 3A

|

A Large Tumor— Esophagram shows a large 6 cm tumor disrupting mucosa and causing a narrowing of the lumen. |

Figure 3B

* Monitoring Response to Treatment-Endoscopic ultrasound is also quite useful for monitoring the response to chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Roubein et al. 53 have shown in preliminary studies that serial endoscopic ultrasound examinations are useful in evaluating the response of esophageal adenocarcinoma to chemotherapy. Only the EUS staging information consistently correlated with histology.53 Tumor area and maximal thickness measurements on endoscopic ultrasound did not correlate with those on barium studies in these patients, and the EUS findings proved to be more accurate. Two other studies 54,55 showed that endoscopic ultrasound could accurately assess response to treatment. However, one of these studies indicates that EUS may be less useful in radiotherapy evaluation than in evaluating response to chemotherapy due to radiotherapy-induced inflammatory and fibrotic changes.55

In patients that are poor surgical risks, endoscopic ultrasound may be used to determine which early carcinomas are superficial enough to be treated with laser. Figures 4a and 4b show a superficial mucosal carcinoma. The muscularis propria is intact and no lymph nodes were seen. The patient underwent laser therapy to ablate the tumor. Follow-up endoscopic ultrasound and biopsies over the next two years were negative for tumor. The patient remained asymptomatic.

Figure 4A

Figure 4B

Endoscopic Ultrasound in Evaluating Gastric Carcinomas

Screening endoscopy with biopsy is the procedure of choice to evaluate suspicious gastric lesions. Except for tumors that do not break through the mucosal surface, such as linitis plastica, conventional endoscopy is superior to endoscopic ultrasound for diagnosis. Endoscopic ultrasound measurement of wall thickness for gastric tumors is more difficult than for tumors of the esophagus because of the variability of the angle at which the ultrasonic waves hit the gastrointestinal wall. In the esophagus, the scope is usually parallel to the wall so that the sonographic plane and the wall are perpendicular to each other for optimal imaging.

Although endoscopic ultrasound is up to 6 times more accurate in staging tumors than CT, 24 differentiation between benign and malignant wall changes is often difficult, if not impossible with EUS. This is particularly true when trying to evaluate a biopsy-negative, large gastric ulcer. A few studies evaluating EUS features of benign gastric ulcers have shown that changes of the wall layer structures resembling malignancy occur in the course of ulcer disease. 56 Inflammatory changes secondary to ulceration often result in overstaging, but understaging by endoscopic ultrasound is only about 5%.9 However, since CT cannot evaluate the muscularis propria, endoscopic ultrasound is the only reliable nonoperative means of assessing tumor depth and extension until a tumor is very large. Although CT sometimes can detect distant metastasis and lymph nodes, endoscopic ultrasound will be more accurate in staging, especially for these distant N2-nodes.

Many patients with gastric carcinoma will require surgery for palliation of bleeding or obstruction. In addition, the prognosis for patients with regional lymph node spread is not much different from other patients with gastric carcinoma except those with very early or very late stage disease. Therefore, resection is usually attempted unless there is evidence of widespread metastatic disease. Surgical staging will be more accurate than staging by EUS. Therefore, at the present time, endoscopic ultrasound will not have much impact on therapy, except for imaging those areas such as the cardia, which may be difficult to evaluate by CT scan

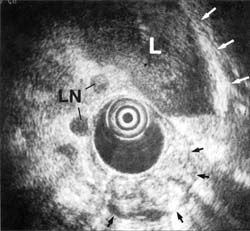

* Two Examples of How EUS Can Affect Therapy-The following are examples where endoscopic ultrasound did change therapy for gastric carcinoma. Figures 5A, 5B, and 5C illustrate a 67-year-old male in whom endoscopy revealed a small flat tumor in the cardia. Esophagram showed only minimal inflammatory changes. CT did not reveal any evidence of tumor. Endoscopic ultrasound, however, showed extensive tumor that had invaded the diaphragm. In addition, many lymph nodes meeting all criteria for metastatic spread were found. Surgery was cancelled and nonoperative treatments instituted.

Figure 5a

Figure 5b

Figure 5c

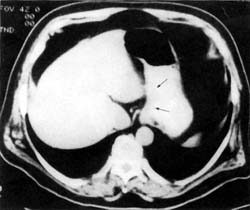

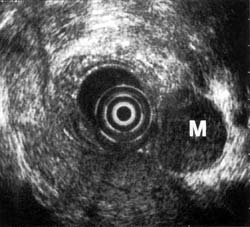

CT in the patient illustrated in Figure 6 showed a proximal gastric mass, with ill-defined margins, between the aorta and the mass indicating nonresectability. Endoscopic ultrasound showed the tumor mass was in a hiatal hernia to the right of the aorta, without invasion. It also showed an enlarged large lymph node to the left. The tumor was resected.

Figure 6

Since EUS has been shown to be more accurate than any other nonoperative technique in staging gastric neoplasms, it will be important in clinical trials requiring accurate preoperative staging. Although it is known that prognosis depends on depth of tumor invasion, presence or absence of lymph node metastasis and distant metastasis, studies are needed to determine whether prognosis is affected by preoperative vs postoperative chemotherapy plus radiotherapy. In addition, if recent reports 37 of endoscopic treatment of early cancer continue to show good results, endoscopic ultrasound may become integral in excluding transmural growth of these tumors.

For gastric as well as other carcinomas, EUS appears to be important in the postoperative follow-up to diagnose residual disease or recurrence.57 Until recurrent tumor is well advanced, CT is unable to reliably differentiate postoperative changes from tumor. Figure 7 illustrates a large perigastric mass, which, on CT, could not be differentiated from a loop of bowel that had not filled with barium. Laparoscopic biopsy confirmed the mass to be a large malignant lymph node.

Figure 7

Use of Endoscopic Ultrasound to Image Lymphomas

Endoscopic ultrasound is extremely accurate in staging non-Hodgkins lymphoma of the gastrointestinal tract. 28,29 Even when CT is negative, endoscopic ultrasound is able to distinguish different stages of the tumor. In addition, endoscopic ultrasound can be used to monitor the progression of the disease during chemotherapy. Endoscopic ultrasound also is the only technique able to demonstrate complete disappearance of the intramural infiltration and reappearance of the normal five-layer wall architecture.

Endoscopic Ultrasound in the Imaging of Submucosal Tumors

Submucosal tumors of the gastrointestinal tract are most often detected by barium radiologic examination or endoscopy. Standard endoscopic biopsies usually do not demonstrate any abnormality, since the lesion is under the mucosa. Nor does CT add any additional information about these lesions. Endoscopic ultrasound is the only imaging technique available that can detect the 5 layers of the gastrointestinal wall, as well as abnormalities of these layers such as thickening or obliteration of layers. Therefore, EUS can accurately define the origin, extent, and depth of invasion of submucosal tumors. 26,27

Figure 8 shows an endoscopic ultrasound image of a tumor that originated from the muscularis propria and met all criteria of a benign leiomyoma. There is a clear, smooth transition from the normal wall into the tumor where the muscularis propria thickens, but the 5-layer architecture is still preserved. In a contrasting case, EUS showed disruption of the wall architecture at the tumor margin (Figures 9A and 9B). At surgical resection, the tumor was found to be a neurosarcoma. The endoscopic ultrasound image is remarkably similar to the corresponding histology.

Figure 8

Figure 9a

Figure 9b

On endoscopy or barium radiography, it is often impossible to determine whether a mass below the mucosal surface is an extrinsic or intrinsic tumor, a vascular structure, or compression from an adjacent organ. Because endoscopic ultrasound can accurately image the gastrointestinal wall and organs in close proximity to the gastrointestinal tract, it is the only imaging technique that will reliably define the nature of a submucosal mass. If a tumor is found, an endoscopic ultrasound-directed submucosal needle biopsy can be performed. This type of deep biopsy is usually essential, since there are no specific sonographic features to differentiate benign from malignant tumors unless there is tumor destruction of the wall architecture. The combination of endoscopic ultrasound with guided deep biopsy 58 or aspiration 59 is very accurate in making a diagnosis.

Endoscopic Ultrasound Imaging of Pancreatobiliary Disease

Endoscopic ultrasound has clearly emerged as the most accurate single test for imaging pancreatic disease. Prospectively, EUS has now been favorably compared with standard ultrasound and CT, 60,61 with ultrasound plus CT and ERCP (endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography), 32,62 with CT and ERCP, 30 with CT and angiography, 40 and with ultrasound and ERCP. 63 These studies show that EUS is more accurate than any other test for diagnosis, staging, and predicting resectability of pancreatic tumors. 64

Identifying the patient with a resectable pancreatic tumor with no metastasis or vessel involvement would spare many a major operation. Operative mortality and morbidity for pancreatic surgery remain high, except in specialized centers. As pointed out by Warshaw et al., 65,66 exploration is not the best way to detemine resectability if the cancer cannot be resected during that same operation, because "the first operation may irrevocably cast the die by violating the cancer or otherwise creating adverse circumstances for later efforts." Even though, at present, resection provides the only chance of cure, 65 accuracy in determining resectability prior to exploration has become increasingly important because of reports demonstrating both effective decompression of biliary obstruction with endoscopic stenting 67 as well as effective palliation with chemotherapy and radiotherapy.17 Improved accuracy in nonoperative small tumor staging will have a significant impact on clinical outcome.30,64

Shortcomings of Other Imaging Techniques-Initial evaluation of suspected pancreatic carcinoma usually consists of CT and/or standard ultrasound, which are equivalent in accuracy when optimally performed. 68-70 However, a direct relationship exists between mass size and the sensitivity and specificity of these tests. 34,65 For lesions that appear localized and small, preoperative evaluation is the most difficult. 65,66,71,72 In a retrospective study by Yasuda et al.,34 ultrasound, CT, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), and angiography were compared with endoscopic ultrasound for evaluation of pancreatic tumors. Angiography, CT and ultrasound were of limited value for lesions less than 3 cm; endoscopic ultrasound, on the other hand, detected 100% of them. For tumors larger than 3 cm, rate of detection for these tests approaches that of endoscopic ultrasound.

Of the present conventional methods for diagnosis of small pancreatic lesions, ERCP appears to be the most reliable, detecting 60% to 80%, depending on size. 72,73 However, some small pancreatic lesions cannot be detected even by ERCP. Endoscopic ultrasound, on the other hand, can diagnose tumors smaller than 2 cm not found by any other imaging techniques (Figures 1OA and 10B). Although CT scan can visualize the pancreas in more than 90% of patients, a tumor must be at least 2 cm to be visible.65,74 Magnetic resonance imaging confers no added benefit, since it does not significantly differ from CT in sensitivity or specificity to pancreatic lesions. 65,75 At least 20% of pancreatic tumors thought to be resectable may not be detectable by CT scan.74

Figure 10a

Figure 10b

In cases of possible pancreatic carcinoma, where CT or ultrasound is negative, jaundice will be an indication for ERCP prior to possible endoscopic ultrasound. Suspicion of pancreatic carcinoma in a nonjaundiced patient is a definite indication for endoscopic ultrasound. CT is not reliable in predicting resectability. When tumors of all sizes are grouped together, CT can be quite accurate in predicting unresectablity.76 However, even these results depend on well-controlled, optimal CT scan technique, with both oral and IV contrast. 74 Also, as the mean tumor size becomes smaller, CT becomes less reliable.

Determining Stage and Resectability-The variable reliability of CT reported by various groups may be attributed in part to differences in the patient populations studied. Freeny et al. 76 reported on all pancreatic carcinoma patients seen at their institution who underwent a dynamic contrast-enhanced CT scan. They found CT to be highly accurate in both diagnosis and staging. Their criteria of unresectability resulted in a 100% positive predictive value. However, most of their patients appear to have had advanced disease. Only nine of 174 patients were thought to have resectable tumors. Of these nine, only one did not have either microscopic involvement of lymph nodes or local tumor extension, making the tumor unresectable. In addition, arterial involvement was found in 99 of 150 patients, and 70 of 150 had varices on CT. These findings are signs of late stage pancreatic carcinoma. Therefore, their conclusion that angiography need not be recommended for tumor staging is valid, but only for such patients with relatively advanced disease, which is well imaged by CT.

Warshaw et al., 66 reporting on a subgroup of patients referred for treatment of potentially curable pancreatic carcinoma, found that angiography did improve accurate determination of resection status when combined with CT. They found that CT alone was only 45% correct in predicting resectability, but tumor sizes were not described. Others 74,77 report that CT scan has at best only a 60% accuracy in assessing resectability, but again, sizes of tumors were not detailed.

Studies that evaluate resected tumor pathology have shown a direct relationship between tumor size and both resectability and stage. Tumors less than 3cm in size were found more likely to be resectable .65,72,78,79 Freeny et al. 76 suggested that once tumors are larger than 3 cm, relative size was not useful in predicting resectability, since few are resectable. Their limited description of locations and sizes of tumors included only 7 (4%) small pancreatic masses that were less than 3 cm and appeared resectable.

Evaluation of suspected pancreatic tumors with ultrasound or CT will accurately stage those larger than 5 cm, 69,70,76,79 relying primarily on distortions of contiguous fat planes. But difficulties arise in evaluating small tumors. Fat planes may actually be unaltered because the tumor is still confined to the pancreas or the planes may appear unaltered because, with tumor associated weight loss, there is an accompanying loss of the fat planes. Also, the density of a small tumor is often so similar to that of normal pancreatic parenchyma that it remains undetected despite thin section CT.

For lesions that appear localized and are less than 5 cm in size (or even not visible) on standard ultrasound or CT, endoscopic ultrasound will provide the information required to select the most appropriate management plan. Performing EUS early in the evaluation of such patients is likely to be effective in terms of clinical utility. Reviewing the data from various studies 64 shows that endoscopic ultrasound will significantly change management in about one-third of patients when it is used in the appropriate clinical setting (Figure 11).

Figure 11

b = ERCP if bile duct stone suspected or EUS not available and jaundice is present.

c= Prelaparoscopy ERCPwith stent if bilirubin either greater than 15 mg/dL or present more than 6 weeks.

d = Preresection angiography and/or ERCP as needed if EUS not available. Combined chemoradiotherapy pre- or postoperatively according to protocol.

e = Gastrojejunostomy for symptoms of impending gastric outlet obstruction. Biopsy confirmation of pathology as needed. Combined chemoradiotherapy according to protocol with attempted resection of patients who are downstaged.

If EUS shows a tumor is resectable, then laparoscopy to exclude small liver metastases, generally not seen on CT, 66,80 may prove beneficial prior to attempted resection. Endoscopic ultrasound is unlikely to provide additional information for patients with tumors larger than 5 cm, 30,60 because the endoscopic ultrasound probe cannot always be brought close enough to a lesion to bring its margins into optimal focus.34 For large tumors, CT scan with IV contrast can reliably confirm the extent of disease.

Diagnosis with fine needle biopsy or, even better, ultrasound-guided core biopsy 81 followed by palliative bypass of biliary obstruction with an endoprosthesis or, depending on local expertise, surgical bypass, is straight forward .67,82 These patients can then be treated with combined modality therapy. With the evolution of successful combination chemotherapy plus radiotherapy for pancreatobiliary tumors of all stages, 15,17,20 improved nonoperative staging will be increasingly important.

A Strong Point of Endoscopic Ultrasound-The extraordinary accuracy of real time endoscopic ultrasound is primarily due to its unsurpassed resolution of the parenchyma of the pancreas and its ability to evaluate and integrate, on the same exam, mucosal, vascular, ductal and parenchymal abnormalities. To obtain information about these four types of abnormalities normally requires endoscopy for mucosa, venogram or arteriogram for veins and arteries, ERCP for ducts, CT or ultrasound for parenchyma and lymph nodes.

The additional information obtained from EUS has been reported to result in a major change in the clinical management of one-third of cases, and to aid in clinical decisions in 75% of cases.30 Compared to endoscopic ultrasound, a successful ERCP will provide superior imaging of the common bile duct and pancreatic duct. However, when ERCP does not visualize a part of the pancreatic duct or common bile duct, this area is usually seen well on endoscopic ultrasound. In addition, endoscopic ultrasound detects vascular involvement by pancreatic tumors as accurately as angiography.31,34,44

* Limitations of Endoscopic Ultrasound-Present limitations of endoscopic ultrasound include:

1. A short optimal focal range of only 4 cm.

2. The echo pattern and features of various pancreatic diseases and lymph nodes can appear similar; consequently, criteria to distinguish diseases overlap. Endoscopic ultrasound is, at present not able to reliably differentiate focal chronic pancreatitis from carcinoma.56 Although EUS can be helpful, this is still a diagnostic problem that requires several imaging tests, even laparotomy.

If other imaging techniques diagnose chronic pancreatitis, endoscopic ultrasound may add little information to an ERCP or CT scan. However, evolution of image interpretation as well as equipment improvements will further increase the accuracy of endoscopic ultrasound.

Endoscopic Ultrasound for Imaging Carcinoma of the Colon

Most patients will undergo attempted resection unless there is evidence of widespread metastatic disease. With the introduction of new surgical techniques, the operation performed will depend on accessibility and size of the tumor. If the lesion is localized without spread to lymph nodes, local excision and sphincter-saving procedures can be done. A significant improvement in staging accuracy 36 was found for endoscopic ultrasound (95%) when compared with digital examination (62%) and CT (71%). The combination of EUS to assess tumor extent and digital exam to assess mobility should enable precise planning of surgical treatment as well as define who may benefit from chemoradiotherapy, either as the sole treatment or as an adjunct to surgery. 39,84

In patients who do not undergo resection, local treatment has been successful for palliation and even cure.37 Endoscopic ultrasound is the only method that can accurately evaluate the extent of local disease for lesions too small to be seen by other imaging techniques.

Finally, when biopsies of the anastomosis are negative, postop evaluation for recurrence without endoscopic ultrasound is difficult, since CT cannot reliably differentiate postoperative changes from tumor recurrence until the disease is well advanced. Endoscopic ultrasound has been shown to accurately predict tumor recurrence.85,86

References